California

can not begin to solve its structural budget deficit problem without first

addressing the fundamental issues of health care’s structure and cost.

It’s

Time for Fundamental Health Care Reform

By David J. Gibson, MD

|

|

California

can not begin to solve its structural budget deficit problem without first

addressing the fundamental issues of health care’s structure and cost. |

A consensus is forming.

California can not begin to solve its structural budget deficit problem

without first addressing the fundamental issues of health care’s structure and

cost. For years we have been avoiding the need for a substantive policy debate

by concentrating our attention upon how we should pay for the current system.

Further debates over single payer vs. private health plans will not lead

to a resolution of California’s structural budget deficit problem.

The longer we delay in joining this debate, the more likely it will be

that California’s budgeting process will continue to spiral out of control and

will ultimately lead to the State’s insolvency.

A consensus is forming.

California can not begin to solve its structural budget deficit problem

without first addressing the fundamental issues of health care’s structure and

cost. For years we have been avoiding the need for a substantive policy debate

by concentrating our attention upon how we should pay for the current system.

Further debates over single payer vs. private health plans will not lead

to a resolution of California’s structural budget deficit problem.

The longer we delay in joining this debate, the more likely it will be

that California’s budgeting process will continue to spiral out of control and

will ultimately lead to the State’s insolvency.

The

cost trend indicator warnings have been sounding for some time.

Health expenditures per person rose 32% between 2000 and 2004 and

continue to outpace the rest of the economy. The accompanying graph illustrates

the crushing burden America’s health care system places upon the economy.

By 2013, health care expenditures are expected to double, with an

estimated 18% of the domestic economy devoted to healthcare.

In 2004, Medicaid cost the

states and the federal government more than $300 billion.

This year the program is projected to cost the federal government alone

over $190 billion with the combined state and federal

projected expenditure to be roughly double this number.

According to the National

Assn. of State Budget Officers, spending on Medicaid grows by around 8% a year

on average, while total state spending grows an average of 4.5%.

This growth is outpacing state revenues and is now a larger component of

total state spending than elementary and secondary education combined.

This program alone is driving most of the states toward insolvency. Complicating the state’s Medicaid problem, the federal

government is indicating that it will likely lower the federal contribution to

the program next year in its drive to reduce deficit spending.

The public is becoming aware

that the above trends are not sustainable.

As a result, we are now hearing calls from across the political spectrum

a call for “fundamental” change in health care; but, before we begin

discussing fundamental changes within the health care system, it would serve us

well to examine what this change will involve.

The

current system’s structure

We should begin this

discussion by understanding that health care’s cost structure is based upon an

artificially constructed market foundation. What we now have in America is a

pricing structure for health care that is based upon the best funded payer’s

ability to pay (the employer and the government) rather than what patients and

their families can ever afford. This

has produced inflationary trends that are completely independent of the market

forces that discipline the rest of America’s economy.

We also have an acuity based

health care system that spends most of its resources in the last two weeks of

life. In essence, we try to use medicine to defeat death. Of course, this does

not work.

Both of the above realities

define our current health care system and represent an irrational foundation for

America to have used in building its current health care system.

As we begin this process of

examining fundamental changes, we must not confuse the terms fundamental with

incremental. Getting something of value in return for concessions in a

negotiated framework will not work. “Fundamental” reform requires focusing

on the patient and his or her needs — not what benefits those making money in

the current system will continue to exploit.

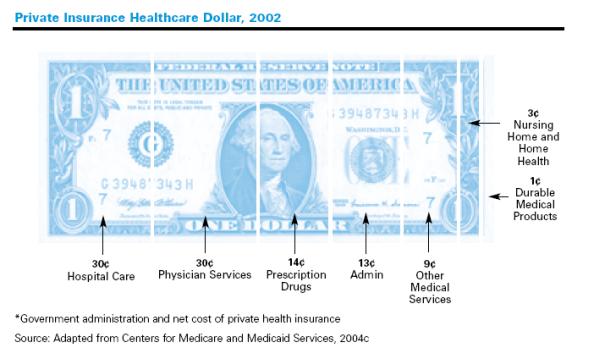

The primary inflation drivers

in health care are illustrated in the accompanying graph[1]

and include hospitals, pharmaceutical manufacturers, health insurance companies

and the cost of labor. These are the areas where fundamental reform needs to

begin in the industry. Reform outside the industry such as unfunded mandates by

the legislature and America’s tort system will be required as well but will

not be examined in this article.

Hospitals

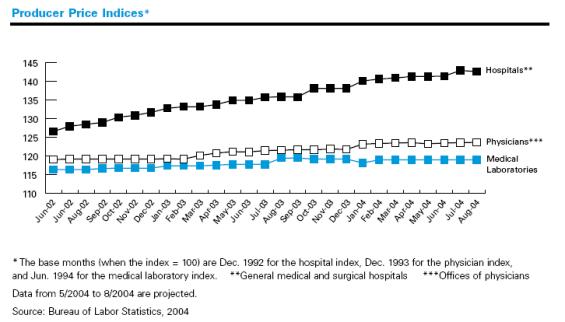

More than half of the

increase in private insurance spending has been driven by outpatient and

inpatient hospital cost. Outpatient costs were the single largest contributor to

increasing premiums in over the past several years.

While prices for physician and laboratory services rose about 2%-4% from

June 2002 through August 2004, hospital prices rose 13%.

The following graph[2]

illustrates this relative cost trend.

As we evaluate the role of

the hospital in the evolving health care system, we need to revisit the outdated

idea of isolating the sick and dying from the community. This concept originated

in medieval times to protect society from the sick. This paradigm simply does not translate into the era

of antibiotics.

For starters, it is a foreign

concept. America’s commitment to

an individual’s freedom makes it averse to the very concept of custody.

Taking custody of an individual is the most costly and least productive

of options for treating the sick and dying. In that technology is driving health

care to the ambulatory setting, the system should be designed with less

dependence on institutional care in the future.

Transitioning from an

inpatient, acuity-oriented system to an ambulatory-based system will require

focusing upon these policy issues:

·

Deconstruct

regional hospital oligopolies. It was a major policy

mistake, made by the federal courts over the objection of the Clinton

Administration, to let hospitals coalesce into dominant regional corporations.

More than half of the nation's hospitals belong to larger health-care systems.

Recent studies demonstrate that consumers are disadvantaged in that these

systems drive increased cost to the consumer.[3]

Northern California is dominated by two of these regional systems (Sutter

and CHW) and has some of the highest health care costs in the western United

States as a direct result. These oligopolies should be dissolved.

·

Make

rural hospital monopolies public utilities. In communities with only one

hospital (Marysville, Crescent City, etc.), the hospital should be regulated as

a utility and managed as such. In a utility paradigm, the hospital would be

required to get permission from the people it serves to set charges. These

hospitals now prey on their local communities and destroy rural economies.

·

Prevent

hospitals from expanding into the ambulatory market. Over

the past two decades, hospitals have used the most expensive resource in health

care, their inpatient bed, to leverage contract advantages with managed care

companies. In exchange for inpatient bed discounts, hospitals have been able to

gain a dominant position in the delivery of ambulatory diagnostic and

interventional services (outpatient surgery center and radiation units, etc.).

They have brought their high overhead, monopolistic management style into this

setting and stifled innovation while exacerbating the inflationary problem in

health care. Hospitals should not be allowed to provide services in the

ambulatory market. Furthermore, managed care companies should be prohibited from

linking inpatient discounts with preferred outpatient diagnostic and

interventional contracts.

·

Prohibit

hospital-affiliated doctor groups.

Permitting

hospitals to develop affiliated medical groups was also a public policy error.

Affiliated groups align the physician’s business interests with the hospital

in the latter’s never-ending battle with health insurance companies.

The cacophony of battle between Sutter and Blue Shield (representing

CalPERS) speaks to this issue. A physician’s loyalty represents a long term

commitment to his or her patient and far transcends annual contract

negotiations. Physicians should immediately disassociate their medical groups

from hospitals.

·

Break

up the Emergency Room monopoly. Hospitals and ER medical groups have

leveraged their contract position with third party payers so that professional

fees for similar services are marked up by a factor of three over all other

alternatives in the ambulatory setting. Furthermore, the hospital marks up

supplies such as pharmaceuticals by a factor of ten or considerably more.

Stacking the reimbursement system in such a distorted way makes the ER the only

option after hours or on weekends. There is no incentive for physicians to

create cost effective after hours alternatives. These disproportionate

reimbursement structures should be eliminated.

·

Make

hospitals participate in the safety net for the poor, or pay taxes.

Not-for-profit

hospitals should rediscover their only

mission – to care for the poor. Not-for-profits

were not designed to compete in the for-profit market. Spending on a technology

arms race and pouring money into advertising is a diversion from their

fundamental mission. Complaints by non-profit corporations over their safety net

responsibilities are unseemly.

Another health care player

reporting record earnings is the health insurance industry. Underwriting health

care is, at best, a minor peripheral activity for these companies. Most of their

activity is focused upon intermediation of health care transactions. There are

far more efficient alternatives in the market today.

Perhaps the most insidious

effect of managed care has been the insurance company development of discounted

provider networks. These networks

now disadvantage the individual patient who pays cash. This disadvantage

translates into a fiscally dangerous environment for the 44 million Americans

without health insurance as they confront the health care system.

This discount structure is

counterintuitive. No other sector of our economy marks up fees for cash customers. In addition, these networks reward the

status quo, guarantee hospital hegemony and inhibit any incentive to innovate.

Health insurance companies

have no other core competency outside these networks. Their adjudication of

claims and financial intermediation of services use analog technology discarded

by the financial services industry two decades ago. This outdated technology has

inhibited the deployment of digital technology in health care.

Health insurance companies

have utterly failed as intermediaries. On their watch, inflationary trends in

the industry have been well above all other segments of the economy.

Eliminating insurers as

intermediaries in health care would be a positive outcome in a new fundamentally

restructured health care system.

Prescription

drugs and hospital outpatient costs have been the fastest growing components of

privately funded healthcare costs for the past decade.

For this reason alone, pharmaceutical costs and industry structure can

not be omitted when health care reform is implemented.

As we open this subject, it

is important to understand that the core competency of pharmaceutical companies

is not research, but marketing. The debate over stem cell research illustrates

this. There is no ban on privately-funded stem cell research anywhere

in America. There is a restriction on federal funding for some of its

components.

If they chose to do so,

pharmaceutical companies could devote unlimited amounts of basic research to

stem cells. Of course, they have not done so in the past and will not in the

future.

Dr. Marcia Angell, the former

editor of the New England Journal of

Medicine, has documented[4] that most of the current

pharmaceutical breakthrough products on the market were developed from basic

research funded by the National Institutes of Health in academic centers.

Pharmaceutical companies then appropriated these publicly funded research

efforts and brought products to the market under exclusive patent protections.

The marketing emphasis in

pharmaceutical companies is evident by where they do invest their resources.

Marketing expenditures of the drug industry

have been estimated at $12 billion to $15 billion every year, or about $8,000 to

$15,000 per physician. There are

nearly 90,000 drug company salesmen in the United States, about one salesperson

for every 4.7 office-based physicians. A

2001 survey found that an estimated 92 percent of doctors received free drug

samples from companies; 61 percent received meals, tickets to entertainment

events, or free travel; and 12 percent received financial incentives to

participate in clinical trials.[5]

It is now becoming evident

that the pharmaceutical industry is morphing into an entirely new structure.

This transition is traumatic for the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, there

is great harm now being inflicted upon health care as old pharmaceutical

companies resist change.

All the large manufacturers

have business models built on delivering “block buster” products to the

market. Block buster products target common health problems and are prescribed

by generalist physicians. Examples include: Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) for

gastrointestinal ulceration; Selective Serotonin

Re-uptake Inhibitors (SSRI) for

depression; and HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A) reductase

inhibitors, referred to as Statin products for hypercholesterolemia.

Most of these “low hanging

fruit” products have been introduced to the market and either have, or soon

will, lose patent protection. The current pipeline for new products is

inadequate to sustain the pharmaceutical companies and investors are reacting.

In late 1998, pharmaceutical stocks traded at 40 times their expected earnings

for the following 12 months. Today,

these stocks trade at less than 14 times their expected earnings, the cheapest

level in eight years. It is clear

that an era is passing. This

situation is analogous to Pan American Airlines which no longer flies chiefly

because its business model did not translate into a fundamentally changed

airline market.

These

multinational pharmaceutical companies are now consolidating while they

compensate for their pipeline deficiencies by marketing “me

too” products. They are also modifying previously introduced products that are

losing patent protection with minor molecular modifications. This strategy

isn’t working.

In

reality, these companies are failing because they lost their ability to

innovate. Over the next decade, most of these old companies will either

disappear or morph into delivering high-margin, lifestyle-enhancing drugs such

as Viagra or Propecia to the market.

The truly innovative new

products coming to market are being developed by small new companies that

generate “orphan” drugs. These products serve only a small number of

patients and are generally prescribed by specialists. Most of the

biologic-produced products, such as Remicade, Enbrel and Humira,

fit into this category. All of the genetic targeted and derived products will as

well. Block buster business models will not deliver these new products at

affordable prices.

The

sooner these older block buster-based companies give way to new companies with

new business models, the better it will be for health care. Society has

entrusted physicians with the exclusive responsibility for prescribing, and it

is incumbent upon us to not allow these older companies to inflict further

damage on America’s health care system as they fail.

Any physician prescribing a

brand product over a generic without head-to-head proof of its superiority,

documented in a national peer-reviewed journal, is doing a disservice to his or

her patient and to America’s health care system.

Resonating through all of

these issues is the reality that the cost of labor in health care is too high.

Before the advent of third-party payers, America’s health care system relied

on the patient and his or her family to pay their health care bills. There was

no inflation problem in health care when the patient paid the bill. Consumers

policed costs far more effectively than have third parties under the current

system.

Paul Starr in his book, The

Social Transformation of American Medicine, documents that doctors

throughout American history have traditionally had meager incomes. In fact,

doctor incomes were roughly commensurate with a school teacher prior to the

advent of third-party payment. The rest of the labor components in the system

were structured proportionately.

As America’s health care

financing system moves away from first dollar coverage and toward higher

front-end payments by patients, most families cannot afford a labor cost

structure that is out of line with the society it seeks to serve.

So, how do we realign the

labor cost structure in health care? We should start with professional licensure

laws. These laws provide one of the primary supports for today’s bloated labor

cost structure in health care.

Professional licensure was

originally developed to protect the patient. It no longer serves that purpose.

Licensure now insulates labor in health care from competition and inhibits

innovation. This is featherbedding at the expense of the patient. It restricts

the availability of culturally and ethnically suited support for the patients in

our evolving society.

Today, the only real purpose

of license defined scope-of-practice is to raise money for politicians. Each

year doctors fight with dentists before the Legislature over how far into the

neck the latter can treat. The same goes for doctors and podiatrists — how far

up the lower leg can the latter go? Defining clinical competence through the

political process is nonsense.

It is no secrete that the

Legislature holds annual “juice sessions” to exploit these

inter-professional conflicts and thereby raise campaign money. This is obscene.

The process serves no useful purpose and should be stopped.

In short, the entire purpose

of licensure and scope-of-practice needs a thorough re-evaluation from the

perspective of what is good for the patient rather than what serves the

interests of the labor force in health care.

It is time to get serious

about “fundamentally” reforming health care. Not doing so will only

perpetuate our self-created culture of delusion. Health care’s inflationary trends will destroy the

financial structure for the State of California in that these trends are not

sustainable. All of organized

labor’s valued private health plans will also be swept away as health care’s

cost trends demand more and more limited resources. In reality, policy makers have no alternative.

They must reform the health care system in the near future.

We can no longer perpetuate

an acuity-based system whose foundation is built upon outdated custodial

institutions. We can no long permit health insurance contracts to warp the

incentives in health care and stifle innovation. We dare not let failing pharmaceutical companies inflict

further damage and we cannot accomplish any of this without bringing health

care’s labor cost structure into line with the rest of our economy.

We have learned that the

system can not be reformed from within. The

players within health care will always opt for more funding rather than reform.

Unfortunately, there is no end to the more funding option.

If 18% of the GDP by 2013 does not adequately fund health care how much

will the industry demand. Will 25%

suffice? How about 50%? Of course we could not educate our children or defend the

country. We live in an era where

health care must co-exist with the rest of America’s economy.

Clearly waiting for internal reform is folly.

We need to devolve

America’s health care system into a less complex and costly structure that

patients and their families can understand and actually pay for. In reality,

there is no choice. Without truly fundamental reforms, our economy cannot

sustain the inflationary juggernaut we have unleashed.

DJGibson@illuminationmedical.com

[2]

ibid

[3]

Health Affairs, Vol 24, Issue 1, 213-219

[4]

“The Truth About the Drug Companies;” M. Angell; Random House; ISBN

0-375-50846-5

[5]

Doctors

and Drug Companies;

David Blumenthal; NEJM; Volume 351:1885-1890; Number 18. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/extract/351/18/1885